So, the only theme park I've ever been to is Wild Waves, which is really just a collection of rides and has no identifiable theme other than 'water', although not all of the rides are water, so that isn't really accurate, either.

If we're going to talk about the hyperreal in the context of theme parks, how does that work? Using the examples of Disneyland/world, the Wizarding World of Harry Potter (more commonly referred to as "Harry Potter Land") or other themes, how does the park create its supposed hyperreality?

These parks operate under the assumption that they will be accepted by the public as real, especially children. Given the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, (though I have not been to any of these parks, I am by far the most familiar with the Wizarding World) we can look at how the park is advertised.Click here to visit the park's webpage

The park is clearly not real. Adults and children of all ages alike are aware of this. Hogwarts is located in Scotland, and even if you don't know this, you know it's somewhere not in Florida. The only people who might be fooled by this are age four and under. Yet, adults and children do not act like the Wizarding World is in any way unreal. They participate in the world, interacting with the workers, asking questions in British accents, and immersing themselves fully into the fake reality around them. I guess what I'm trying to get at here is that, although there is a knowledge of the fakeness of parks like this, there is also the initial acceptance upon entering that, while within the park, it is reality. And, in a sense, it is more real than the reality outside.

A theme park would not be able to operate under the assumption that nothing within is real. Instead, there is acceptance - for a day, a weekend, or even a whole week - that, even just for now, this is what reality is. In contrast to Baudrillard, this begins to make the real world seem less all-encompassing, less interactive, and ultimately less real.

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Saturday, April 27, 2013

Hyperreality

The article below theorizes that there was a common theme of hyperreality in the movies of the 90s such as Schwarzenegger films, The Matrix, Memento, and Star Wars, to name a few. Even without reading the article, do you think that these movies could be examples of hyperreality?

http://www.americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2010/laist.htm

http://www.americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/spring_2010/laist.htm

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Portfolio 7

In 1621 Robert Burton published Anatomy of Melancholy, a text significant in its attempts to move nervous disorders from classification as physical afflictions to psychological ills. It was in that text that hysteria, already thoroughly explicated by Elizabethan authors Weyer and Jordan, was classified as a fit of the “Mother” occasioned by physical maladies coupled with extreme stress. It is important to note that Burton, following the conviction of his time, averred that the lower a woman’s social class, the less likely her affliction by hysteria. It was, by all accounts, a rich woman’s disease. So it is with Ophelia. By Act IV, scene 5, Ophelia is well-progressed into madness. An Elizabethan audience would doubtless see the signs of hysteria and witchcraft. It is important to note, however, that Shakespeare, responding, perhaps, to the medical developments of his day, complicated the notion of madness. The gentleman describing her affliction states: “her speech is nothing, / Yet the unshaped use of it doth move / The hearers to collection; they aim at it, And botch the words up fit to their own thoughts.” It is possible, of course, that Shakespeare refers to the infectious nature of madness. However, it is also possible that the “hearers” are only constructing Ophelia’s hysteria, ignoring her true ailments in favor of their presuppositions. So it is that Ophelia enters with the phrase “Where is the beauteous majesty of Denmark?” In so doing, she summarizes the entire play as well as the opening query “Who’s there?” Ophelia’s question is aimed at the location of greatness, in persons, in families, in systems. In asking as to the vestment of majesty, Ophelia in fact locates the conflict of the play with more accuracy than any character in the scene, thus demonstrating the Elizabethan potential for the hysterical woman to act as a kind of oracle.

In 1621 Robert Burton published Anatomy of Melancholy, a text significant in its attempts to move nervous disorders from classification as physical afflictions to psychological ills. It was in that text that hysteria, already thoroughly explicated by Elizabethan authors Weyer and Jordan, was classified as a fit of the “Mother” occasioned by physical maladies coupled with extreme stress. It is important to note that Burton, following the conviction of his time, averred that the lower a woman’s social class, the less likely her affliction by hysteria. It was, by all accounts, a rich woman’s disease. So it is with Ophelia. By Act IV, scene 5, Ophelia is well-progressed into madness. An Elizabethan audience would doubtless see the signs of hysteria and witchcraft. It is important to note, however, that Shakespeare, responding, perhaps, to the medical developments of his day, complicated the notion of madness. The gentleman describing her affliction states: “her speech is nothing, / Yet the unshaped use of it doth move / The hearers to collection; they aim at it, And botch the words up fit to their own thoughts.” It is possible, of course, that Shakespeare refers to the infectious nature of madness. However, it is also possible that the “hearers” are only constructing Ophelia’s hysteria, ignoring her true ailments in favor of their presuppositions. So it is that Ophelia enters with the phrase “Where is the beauteous majesty of Denmark?” In so doing, she summarizes the entire play as well as the opening query “Who’s there?” Ophelia’s question is aimed at the location of greatness, in persons, in families, in systems. In asking as to the vestment of majesty, Ophelia in fact locates the conflict of the play with more accuracy than any character in the scene, thus demonstrating the Elizabethan potential for the hysterical woman to act as a kind of oracle.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Let's Talk About Dove's "Real Beauty Sketches"

Most of you have probably seen this already. For those of you who haven't, this is a Dove (soap/beauty products, etc.) project that just recently went viral. Please watch it.

Well, WWWT? (What Would Woolf Think) Or de Beauvir? Cixous? Any of the feminists we've talked about? None of our readings focused too much on the pressure for females to be beautiful. So, in what other ways would these critics respond?

Would they feel that women have been Othered? Are they mysterious? Are they compulsively heterosexual? Why does the artists have to be male? How would they criticize? Would they praise this video at all?

I'd like to hear your thoughts.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Horkheimer, Adorno, and the Pinnacle of Capitalism

Let's take popular music as our example of capitalism. Obvious. Let's take a look at how in it, "all our mass culture is," as Horkheimer and Adorno put it, become "identical,"and how "the lines of its artificial framework begin to show through." Capitalism, which has for so long been telling us it creates products based on consumer need, is having to make such claims less and less. Soon, we will be sold rubbish, even though we know it's rubbish, even though it will cost us. Why? Because, they told us we wanted it, that's why.

And this was all written in 1947. Couple this idea with the idea of progress so ubiquitous in the discussion of capitalism, and add in the acceleration of change in the last few decades, and it seems to me we should be at about critical mass. By now, we should have an example of rubbish we don't need or want but buy anyway. We should have the perfect product of capitalism.

So here's my theory: it's Ke$ha. KE-Dollarsign-HA. And I realize that people have said this about popular music in every genre and every decade since Horkheimer and Adorno, but I think Ke$ha has brought it into a new level. And here's why:

1) The recycled beats. Not only are the backgrounds to Kesha's songs cliche copies of other songs in her genre, some are acknowledged as being almost exactly the same. This has happened more than once. Music producers lose no money on creating new tracks, and fans eat it up. It's an old song that happens a lot in the music world, but Kesha's tracks are unapologetic.

2) The auto-tune. The Machine need not find an artist with vocal talent when it can easily find one that it can auto-tune into a top-selling timbre.

3) The look. She's known for her over-the-top costumes and makeup. What this does two things. a) It draws attention away from what Kesha actually looks like, and b) it draws attention to the products she uses. She could be conventionally pretty, but she no longer needs to be in order to sell. The Machine is therefore saved the trouble of finding a talented, attractive, creative starlet to exploit. It now only needs to find someone to auto-sing over pre-created tracks and wear the body paint and fake eyelashes that the label intends to sell. Kesha is made into less of an individual and more of a character that anyone willing to wear the costume could play.

4) The lyrics. Most are familiar with Kesha's "brush my teeth with a bottle of Jack," or her "the party don't stop till I walk in." Her songs are about living large and partying hard, and there always seems to be an abundance of brand-name alcohol and body glitter (Did I mention Kesha has her own line of body glitter?) in these parties. The moral of the story: More products=better party. And they lived happily ever after, children.

So, we've done it, folks. We've created the perfect sell-able formula for capitalism: recycled tracks + auto-tune + face-hiding makeup = a "human" product (music) without any need for a specific human. People become commodities, and twelve-year-olds buy more glitter.

Do you buy it? Is the pinnacle of capitalism someone/thing else? Am I even asking the right questions?

And this was all written in 1947. Couple this idea with the idea of progress so ubiquitous in the discussion of capitalism, and add in the acceleration of change in the last few decades, and it seems to me we should be at about critical mass. By now, we should have an example of rubbish we don't need or want but buy anyway. We should have the perfect product of capitalism.

So here's my theory: it's Ke$ha. KE-Dollarsign-HA. And I realize that people have said this about popular music in every genre and every decade since Horkheimer and Adorno, but I think Ke$ha has brought it into a new level. And here's why:

1) The recycled beats. Not only are the backgrounds to Kesha's songs cliche copies of other songs in her genre, some are acknowledged as being almost exactly the same. This has happened more than once. Music producers lose no money on creating new tracks, and fans eat it up. It's an old song that happens a lot in the music world, but Kesha's tracks are unapologetic.

2) The auto-tune. The Machine need not find an artist with vocal talent when it can easily find one that it can auto-tune into a top-selling timbre.

3) The look. She's known for her over-the-top costumes and makeup. What this does two things. a) It draws attention away from what Kesha actually looks like, and b) it draws attention to the products she uses. She could be conventionally pretty, but she no longer needs to be in order to sell. The Machine is therefore saved the trouble of finding a talented, attractive, creative starlet to exploit. It now only needs to find someone to auto-sing over pre-created tracks and wear the body paint and fake eyelashes that the label intends to sell. Kesha is made into less of an individual and more of a character that anyone willing to wear the costume could play.

4) The lyrics. Most are familiar with Kesha's "brush my teeth with a bottle of Jack," or her "the party don't stop till I walk in." Her songs are about living large and partying hard, and there always seems to be an abundance of brand-name alcohol and body glitter (Did I mention Kesha has her own line of body glitter?) in these parties. The moral of the story: More products=better party. And they lived happily ever after, children.

So, we've done it, folks. We've created the perfect sell-able formula for capitalism: recycled tracks + auto-tune + face-hiding makeup = a "human" product (music) without any need for a specific human. People become commodities, and twelve-year-olds buy more glitter.

Do you buy it? Is the pinnacle of capitalism someone/thing else? Am I even asking the right questions?

Sunday, April 14, 2013

Gilbert and Gubar

Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar argue that women writers have "an anxiety of authorship." They claim that this anxiety is different than the anxieties male writers have, because while men are anxious in living up to their precursors, women really don't have any percursors to refer to. Woman has to instead worry that her writing will be deemed as unworthy to be read because man will not be able to understand the way in which the woman has written. As a writer, I can say that I am certainly anxious in how my work compares to the works of others, but I have never felt anxiety that my work would be viewed as less because of its distict feminine viewpoint and way of thinking. Was Gilbert and Gubar's statement more applicable in 1979 than it is today? Have any of you experienced what Gilber and Gubar define as the male "anxiety of influence" or female "anxiety of authorship?"

Saturday, April 13, 2013

A portrayal of women Simone de Beauvoir might approve of?

I decided to see if I could find an example of contemporary culture that tried to fight agaisnt the myth of woman as the other. The Dixie Chicks are often considered for songs about woman empowerment, and I think that Simone de Beauvoir might agree with their songs to a large degree. For example, the songs "Cowboy, Take me Away" and "Wide Open Spaces" are primarily about a young woman wanting to be free. Even the song "Cowboy, Take Me Away" is not so much about being with a man as it is about being free. In fact, no males appear in the music video. Woman is seen first as a free being in and of herself, and is not defined based on her actions or relation towards man. What do you think de Beauvoir would see? Would she agree with what these songs are trying to do or still see too much evidence of the myth of women as other in our culture?http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hntXAO_Rq7c

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

Woolf and the Bechdel Test

In response to today's musings as to whether Virginia Woolf's ideas are still relevant in light of new research (and, of course, the ubiquitous "isn't-femenism-kind-of-over" question), I'd like to take a look at Woolf's "Chloe Liked Olivia" section. Woolf talks about the way literature and media so rarely portray female homosocial situations. When we come across a scene in which Chloe is free to like Olivia, we are startled. Shocked, even: "Do not start," says Woolf, "do not blush. Let us admit in the privacy of our own society that these things sometimes happen. Sometimes women do like women" (899). And though we know that life might work in this way, that women actually do have positive relationships with other women, we've come to accept that movies (or books or anything else) usually do not. Women are shown only in relation to men, only as the Other to men. Woolf suggests that this is the product of fiction written by men who are "terribly hampered and partial in [their] knowledge of women" (899).

And, as we all know, this is absolutely still a thing. In film, especially, women are shown and defined only through their relations with men, which in reality are very small parts of life. So, in response, I offer you The Bechdel Test

Some of you are probably pretty familiar with this test, but I put it here because it changed the way I looked at movies. It's a test used to identify gender bias in fiction, and was created by Alison Bechdel in her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. Here's how it works: for a film to be free of male bias it must 1. contain two female characters [with names] 2. who have a conversation 3. that is not about a man.

In 2011, of all of the films nominated for Best Picture, only The Help passed.

Here's a website with listings of different films. Do your favorites pass?

And, as we all know, this is absolutely still a thing. In film, especially, women are shown and defined only through their relations with men, which in reality are very small parts of life. So, in response, I offer you The Bechdel Test

Some of you are probably pretty familiar with this test, but I put it here because it changed the way I looked at movies. It's a test used to identify gender bias in fiction, and was created by Alison Bechdel in her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. Here's how it works: for a film to be free of male bias it must 1. contain two female characters [with names] 2. who have a conversation 3. that is not about a man.

In 2011, of all of the films nominated for Best Picture, only The Help passed.

Here's a website with listings of different films. Do your favorites pass?

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

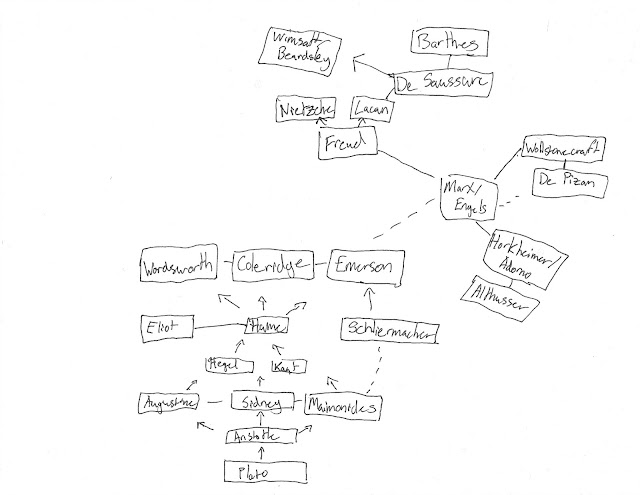

An Explanation of Spittin' Hard

It’s not quite Hegelian to maintain that each generation of

theorists reacts to the excesses of its predecessor. The flow chart of

criticism follows this principle. There are, of course, a few basic

equalizers. You either read Plato or are Plato. You are either male or

de Pizan or Wollstonecraft. The next large shift is simply a function of

whether or not you are going to pay attention to social tensions (a

product of economic tensions) as the governor of human action. If you

are, then you are going to be a Marxist, and if you are not, you are

either going to have to turn to created objects or the natural world.

The former will make you more interesting, the latter will make you

Wordsworth.

Criticism is neither meliorist nor dialectical. It is the

via negative, determining new theoretical movements based upon the

failures of Plato and then everyone else.

Digressions on a Diagram

This diagram is of a tree, but don't be fooled. At first it may seem like those strangely large seeds are growing the tree of thought, and the higher or lower level of thinkers has something to do with progress. That's just Hegelian insistence on some positivistic dialectic model of reality. The tree just has to do with passing time, and is subject for my authorial quips concerning the placement of various thinkers in and around the tree. Also, those seeds, you may notice (as Blaine Eldredge first did) have a level of similarity to the appearance of testicles. That is an unfortunate accident.

I think it's important to note the way that they are in a sort of unified dialogue despite, or perhaps because of their differences. I also notice that's important to not over-value their thoughts. There's this idea that these thinkers are gods, but really there are times when they happen to be petty, or make mistakes, or say things they don't mean. In short, they're human beings. That's a big part of why I made this with a kind of satire or mockery in mind. Many of the catchphrases being over-simplifications or things of the sort. Think of Sidney, who is relegated to a stone beneath the earth. It's not about the insult, its about the realization that these people aren't more than other people.

Theorist Diagram

Tragedy

Plato

-> Aristotle -> Nietzsche -> Freud -> Lacan -> Horkheimer/Adorno

Symbolism/Author’s

intentions

Plato

-> Augustine -> Maimonides -> Hume -> Kant -> Schleiermacher

-> Emerson -> Nietzsche -> Freud -> Lacan -> Eliot ->

Wimsatt/Beardsley

Genius

Maimonides

-> Hume -> Kant -> Hegel -> Wordsworth -> Coleridge ->

Emerson -> Nietzsche -> Horkheimer/Adorno

Education/Societal

Impact

Plato

-> Aristotle -> de Pizan -> Sidney -> Wollstonecraft -> Hegel ->

Emerson -> Marx/Engels -> Horkheimer/Adorno -> Althusser -> Eliot

Most

theorists consider tragedy to be one of the greatest art forms, and they

usually look to Plato and Aristotle’s parameters for what is a good tragedy.

Freud and Lacan take a slightly different approach, as Freud connects tragedy

to the Oedipus complex and Lacan has a more tenuous connection between the

imitation and mimicry in the mirror stage and Aristotle’s definition of tragedy

as a representation of an action. However, neither Freud nor Lacan argue with

any of Aristotle’s rules about good tragedy, and theorists such as Horkheimer

and Adorno have returned to Aristotle and now complain that tragedies have

become more about just punishment than about reversals and the suffering of good

men. A constant problem for theorists is how to interpret symbolism in art, and

how much the author’s intentions matter. Some theorists, such as Hume and

Schleiermacher, think that the author’s background and intentions are vital to

an accurate interpretation of their work, while others, such as Eliot, Wimsatt,

and Beardsley, think that the author is irrelevant once he or she has finished

the work. Augustine and Nietzsche both say that words are metaphors for other

things, and both theorists have theories on how to interpret the metaphors. Freud

and Lacan also believe that almost everything is a symbol representing

something else, often revealing something about the author’s subconscious. Many

theories have been presented regarding symbolism and how an author impacts his

or her work, but none have been proved to be better than all of the others yet.

The

concept of genius has been a steady theme throughout the works of many

theorists. Some theorists directly use the term ‘genius,’ and some simply state

ideas that match other theorists’ definitions of the term. Most often, a genius

is defined as someone who is separate from most of society because of some

superiority, whether it is innate or whether they were chosen to be superior. From

Maimonides’ assertion that only a few can understand to Nietzsche’s Übermensch,

most theorists have some theory of genius. When this theory reaches Horkheimer

and Adorno, these theorists take the idea of genius in a different direction.

In an attack against capitalism, Horkheimer and Adorno say that individuals are

chosen to be special and admired by society, but they are chosen completely at

random and so are in fact not any different from the rest of us. Finally, the

question of how art affects society and how society affects art has been

discussed for centuries with conflicting results. Plato believes that poetry

brings out inappropriate emotions that will hurt society, while Sidney thinks

that poetry supports virtue. Wollstonecraft claims that society educates us,

and Horkheimer and Adorno say that society manipulates and controls us.

Joanna's Flow Chart Midterm Diagram

Hey, fellow Lit Critters! Please click this link: This is my attempt to let you see a more effective and in-focus version of my diagram flow chart thing.

This is the small version of my chart:

This flow chart is meant to map out the relationship of main ideas between these theorists. There are some theorists whose main ideas are not in direct relation to other theorists of their time. Sidney, for example, lived almost 2,000 years after Plato, yet he responds directly to Plato's arguments. de Pizan and Wollstonecraft, though their lines are quite separate from all the others (they follow a rather unique path) are not entirely disconnected. Their particular lines are separate, but they are directly in the middle of the chart, surrounded by the other theorists. These two women wrote about different things than other critics; they focused (especially in our readings) on women's rights. Their prominent ideas might have been separate, but their writing, their rhetoric, and their backgrounds were completely caught up in the writings and histories of these other theorists.

The chart sort of explains itself as you go along, so not much extra explanation is needed. The most multi-faceted section of the chart is "Relationship with who?" This is after the importance of the individual is determined. "Relationships with who?" leads to Others (Master/Slave), The Universal Being, The powerful Ubermensch, The imagination, and Nature. While I previously understood Coleridge, Emerson, and Wordsworth to be related, it was only through this question ("Relationships with who?") that I really understood them. The fact that Nietzsche and Hegel both fit under this headline is fascinating, and it allows me to see them in a different light. This chart is not meant to be the most accurate and complete diagram of theorists' relationships ever. It is a flow chart pointing out possible directions of thought and connection.

Monday, April 1, 2013

Evans Midterm Part 1

Map of Influence

|

| Key |

(Just in case the zoom doesn't work, here is a link to Google Drive: https://docs.google.com/document/d/15TejlYv4vrtX4Yd64BJE2rYO2x5016PR37LjWxKGypc/edit?usp=sharing)

My diagram is in roughly chronological order from top to bottom, with colors marking the different critical groupings (the large red circle, for example, represents Romanticism). Blue arrows indicate that one theorist has marked influence on another. Arrows with red outlines indicate that a theorist was reacting to another (or to the previous critical movement). Under each theorist's name is a brief paraphrase of his or her views on the relationship between art and truth; more specifically, I tried to think of each theorist's answer to the question "how do we judge art?" or "how do we look at literature?" Though these statements obviously do not include all discussed ideas of each theorist, I thought the repetition of these ideas would more clearly show the theoretical evolution from Plato to Althusser.

I suppose I should not have been surprised at the extent to which the texts are interrelated, but I found the relationships staggering. Schleiermacher, especially, seemed to show up when I least expected him, especially in his views about the reciprocal relationship between historical context, language, and art. In a future draft of this diagram, I would want to find a clearer way to represent the relationships between theorists; I realize it is not quite comprehensive, but I feared that adding arrows would make it unreadable. There should be, for example, a very large arrow from Augustine to De Saussure (concerning their discussions of signs), but adding it only made the diagram confusing. Finally, in a future draft, I would want to find a way to connect theorists beyond their critical moments. If, for example, I could find a way to connect the Romantics (Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Emerson) to Schleiermacher in their value of the author, and also group the New Critics and the Structuralists in their dedication to the "Death of the Author," I would be more satisfied. Similarly, if I could group Wollstonecraft, Marx, Horkheimer and Adorno, and Althusser together (because of their tendency toward social criticism), I think it would be more complete. To achieve all of this, however, I think I would have to begin again using a sort of enormous Venn Diagram, a feat I will leave to someone with better academic credentials.

Strausbaugh,Derek's Midterm Diagram

In this diagram, I started at the very beginning, with Plato, because his work interacts with all other critics we have examined. Plato leads directly to Aristotle, who expands and refutes Plato's ideas. The next generation of philosophers, Augustine, Sidney, and Maimonides deal with different aspects of text than Aristotle, but seem to be out of the same critical tradition. I loosely connect Maimonides with Schleiermacher because they both deal with hermeneutics. Emerson also deals directly with Schleiermacher's Ideas.

Hegel and Kant wind up side by side because they both represent huge influential ways that changed the way people though, Hegel with the dialectic and Kant centering goodness around the human being. This leads directly into Hume's ideas of taste, which Eliot runs with. Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Emerson all draw from Hume and his idea of taste, and expand upon that with ideas of how the poet should compose works, and how inspiration works. Marx and Engels splinter off from the romantics, rebelling from the notion that all humanity believes in the same ideals of art, and posit that taste is manufactured in society by those who control production. Horheimer, Adorno, and Althusser expand upon Marx and Engels by getting more specific as to how the society creates its own norms. Similarly, Wollstonecraft rebels against previous notions of taste stating that Gender has been a factor in the past. Pizan is linked to Wollstonecraft in her ideas. Freud is another rebellion from humanity having an innate sense of beauty. He puts for the idea that our psychology and experiences determine what we deem tasteful. Lacan and Nietzsche both draw from Freud, moving his theories into different arenas and expanding upon them. Lacan uses the Idea of the sign in order to accentuate language as a system of symbols. De Saussure take that idea and expand upon it. Wimsatt and Beardsly take that idea to the next level saying that the text is the only thing that matters, because everything that there is to know about a text is in the signs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)